Abstract

Although implementation of inpatient electronic healthcare records (EHRs) in healthcare organizations is nearly complete in the United States and accepted in rural areas and for chronic disease monitoring, this achievement has not translated into consumer-to-business adoption of telehealth for acute concerns in the urban primary care setting. Because there are few studies that describe how and why patients select telehealth, the aim of this study was to learn about perceptions of adult patients in an urban setting when telehealth encounters are available. Research questions included a) How do patients select any type of appointment? b) How do patients perceive and use telehealth options? c) How and when might telehealth be useful in the future?

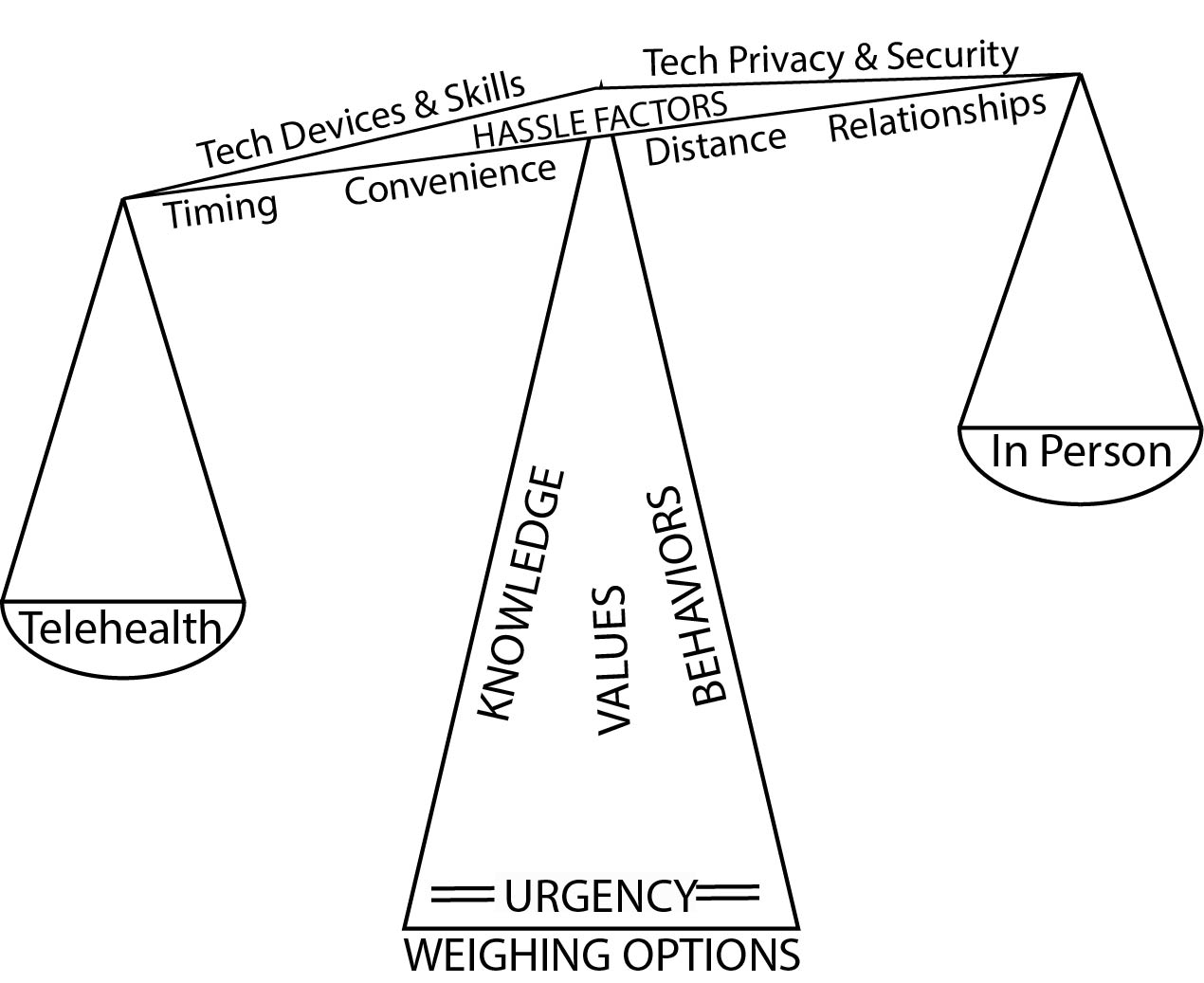

A qualitative study design was used to collect data through semi-structured open-ended interviews from 21 patients in a primary care practice at the end of 2018. Interviews were transcribed and analyzed using grounded theory methodology. The theory of weighing options emerged from the data. The process of weighing options explains how patients balance “hassle factors” of urgency, timing or scheduling, transpersonal relationships, distance, convenience, and various technical aspects before selecting an encounter type. The transpersonal relationship was named a key deciding factor when weighing options. If all factors show a benefit for telehealth, telehealth might be selected.

Implications from this study include facilitating awareness and support with patients for onboarding and using telehealth encounters. Information obtained from the patient perspective may identify strategies for how providers, telenurses, and nurse informaticists may provide caring for patients who choose telehealth encounters.

Introduction

Patients want, need, and deserve the right health care at the right time in the right place, particularly in ambulatory primary care. Barriers to achieving this include lack of insurance coverage, inaccessibility to an optimal provider, and geographic distance (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2019). Telehealth is a wide-ranging solution well suited for meeting these needs, available to make digital connections between patients and providers for almost all aspects of healthcare. However, telehealth adoption by patients in urban primary care for acute concerns is not on par with patient acceptance of telehealth for rural care or chronic care management even though most patients have expressed interest in using technology to connect with providers (Heath, 2017; Wicklund, 2017; Farr, 2018). In 2018, Mercer’s National Survey reported that 71% of U.S. companies with at least 500 employees offered their workers a telehealth healthcare benefit. Yet in 2016, employers reported that only 7% of employees had used it at least once (Umland, Ferreira, & Lown, 2018). By spring 2019, in an astonishing display of incentivizing telehealth encounters for primary care, Walmart dropped the $40 co-pay for virtual visits to $4 for their employees (Walmart, 2019). This hesitation by patients to engage in telehealth encounters has made it difficult for primary care providers to plan accordingly.

Although there is no universally accepted definition of telehealth, this study embraced the wide-ranging definition as adopted by the California Business and Professional Code:

Telehealth means the mode of delivering health care services and public health via information and communication technologies to facilitate the diagnosis, consultation, treatment, education, care management, and self-management of a patient’s health care while the patient is at the originating site and health care provider is at the distant site (California Legislative, 2016).

The term telehealth is also used to describe the modalities of communication, such as real-time or synchronous communication, store-and-forward imaging data between providers, remote patient monitoring, and mHealth (mobile health) using and linking portable devices or the Internet of Things (IoT) (American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing (AAACN), 2018). The term further includes the infrastructure of the necessary technologies (broadband networks, the Internet and social media, niche software applications, computer hardware, smart phones and other smart devices) and processes (video visits, regular telephone calls, faxing, texting, and all types of digital data transmission) (Li & Wilson, 2013; Agate, 2017; AAACN, 2018). Even though telehealth technologies and processes are proliferating, use was still uncommon overall by 2017 (Barnett, Ray, Souza, & Mehrota, 2018).

Zheng, Tulu, Choi and Franklin (2017) noted that successful implementation of telehealth depended on the patient’s willingness to use it. In 2018, the Surveys of U.S. Health Care Consumers and Physicians found the top three reasons consumers did not opt for virtual care were loss of personal connection with their doctors (28%), concerns regarding quality of care (28%), and issues with access (24%) (Abrams, Burrill, & Elsner, 2018). The aim of this study was to explore why ambulatory primary care patients in an urban setting are not selecting telehealth options when rural patients or patients with chronic illness accept and report satisfaction using it.

Literature Synthesis

As technology and medicine have become linked, most research has focused on telemedicine (e.g., diagnosis and treatment only), a telehealth sub-category from the perspective of physicians about the optimal use of technology. Many of those studies described efforts to improve healthcare outcomes, with considerable attention focused on improving geographical access to patients in rural areas. As telehealth expanded, studies in the literature concentrated in one of four areas:

- technology-centric: issues and concerns with design, implementation, and maintenance of the telehealth infrastructure (networking, hardware, software, broadband),

- regulatory-centric: regulatory and legal concerns about software certification, interstate licensing, maintaining personal health information privacy and security, and electronic billing and reimbursement,

- provider-centric: perspectives and needs of healthcare providers using telehealth, and

- patient-centric: limited to healthcare outcomes and satisfaction with telehealth programs and delivery systems.

For this study, the literature review focused on patient-centric studies that were further grouped into two categories according to factors influential to patient acceptance: contextual factors and social factors. It was noted that the reviewed studies only addressed the timeframe from when the patient made contact with a provider to the close of the health care episode or encounter. No studies were found that addressed the process by which patients decide which type of encounter is desired prior to making contact.

For patient-centric contextual concerns, access to telehealth was the most commonly reported, with the most common barrier to access being accommodation (e.g. scheduling) and not geographical as many assume. Wicklund (2017) and Sweeney (2017) argued that geography should not be the only parameter of access, quoting statistics that medical appointments “are just as hard — if not harder — to come by in major cities” (para. 3). Urban access wait times for new appointments are reported to have increased 30% since 2014 (Agate, 2017). This is confirmation that urban patients might also benefit from the same improved access to providers and timeliness of care as provided by telehealth in rural areas.

Patient-centric social factors were identified by Poulsen, Roberts, Millen, Lakshman, and Buttner (2014) who assessed patient satisfaction with a telehealth rheumatology specialist service in rural Australia. They found more than 85% of the respondents identified telehealth as saving time and money associated with lengthy travel for care. However, as is typical with rural telehealth, patients did not use personal devices or the Internet to connect to the specialist in town but used the technology and broadband of the local rural clinic. There was no difference in patient satisfaction for new patients versus established patients using telehealth at such great distances. Polinski et al. (2016) assessed patient satisfaction in a telehealth visit model in which the patient was assisted by the nurse at the distant primary care clinic to communicate with an off-site provider via video conferencing. Given the opportunity to try this type of telehealth visit, patients were very satisfied with the quality of care, convenience, and technology associated with it. Telehealth was found to be as acceptable as a traditional visit, with quality and convenience highlighted as a key feature of acceptability.

Edwards et al. (2014) provided one of the first studies to gather ratings on patient interest in using different types of telehealth. The researchers sought to answer the question if patients with chronic diseases were interested in using telehealth. Regardless of the sociodemographics, the most important factor for engagement was confirmed to be the patient’s confidence in using technology, with a strong preference for phone-based and email-based telehealth.

Other patient-centric research noted positive findings regarding staff support with telehealth. This included telenursing for ancillary services such as case management (Kilbridge, Hood, & Levinthal, 2014) and routine follow-up (Thakar et al., 2018). These and other services of the ambulatory RN are supported by the Telenursing Scope and Standards of Practice for Professional Telehealth Nursing (AAACN, 2018). With the proliferation of the Internet of Things (IoT), remote monitoring by telenurses of patients using wearable technology to manage chronic conditions is becoming more common (Haghi, Thurow, & Stoll, 2017).

IoT and other initiatives in ambulatory care, such as data analytics, represent an expansion opportunity for consultation and support by nurse informatics specialists (NIS). Historically, the hospital has been the setting for nurse informaticians. Arellano (2014) noted five typical functions of the NIS in non-acute care that are incorporated within the American Nursing Association’s Nursing Informatics: Scope and Standards of Practice (American Nurses Association (ANA), 2015). These functions and selected skills include:

- leadership, administration, and management: strategic direction, change management

- compliance and integrity management: data integrity, security, and confidentiality

- analysis: knowledge synthesis, outcomes management

- coordination, facilitation, and integration: project management and optimization

- development: design, iterative development

Determinants of successful implementations and the communicative process in telehealth were evaluated with systematic reviews. Broens and colleagues (2007) conducted a qualitative literature review of 45 papers describing telehealth interventions and identified five major categories of determinants for success throughout the telehealth life cycle. These categories were technology, acceptance, financing, organization, policy and legislation. Broens et al. noted that acceptance by the patient is related to communication of meaningful information that is also personalized. Since acceptance by “required users” (patients and providers) is necessary for any success, all users should be involved in early development of telehealth modalities.

An integrative review performed by Barbosa, Silva, Silva, and Silva (2016) examined 10 studies on the communication process in telenursing. The evaluated studies revealed that “distance imposes communication barriers in all elements: sender, recipient and message and in both ways of transmission (verbal and nonverbal)” (p. 724). The conclusion was that training to develop communication skills for virtual encounters with patients would have an impact on and improve patient acceptance of telehealth.

However, studies were not found describing internal factors when patients select telehealth. Since patient decisions for type of encounter precedes scheduling that encounter, analyzing the process by which patients decide to connect with providers is essential if telehealth utilization is to increase. Because patient motivation and perspectives are largely unexamined for virtual healthcare, knowing when, how, and why patients decide to use telehealth will provide information that ambulatory nurses and providers can use to align clinical offerings with how patients want to use telehealth. This study proposed to fill this gap by answering the questions:

- How do patients select any type of appointment when seeking care?

- How do patients perceive and use available telehealth options?

- Under what circumstances might telehealth be useful to patients in the future?

Ethical Considerations

Permission to recruit patients and collect data was initially approved by the board of directors of the physician-owned medical group where the study was completed, then reviewed and approved by the California State University Fresno School of Nursing Research Committee, meeting criteria for minimal risk IRB review with informed consent. Patients who agreed to participate in the research received individual instruction about the study from the primary researcher and provided written consent. Summaries of interviews were recorded by the researcher without patient identifiers in the recordings or later transcriptions. All study materials were kept in HIPAA-compliant secure locations.

Framework

The conceptual framework of symbolic interactionism (SI) guided the study design since SI focuses on human behavior: people’s thought processes, how importance is assigned to events, and how they choose to interact with the world because of their beliefs and experiences (Chenitz & Swanson, 1986). The researcher’s attempt to understand, describe, and discover phenomenon of interest strictly from the perspective of patients’ own experience is well served by SI. This framework provides an opportunity to discern the importance of telehealth to patients and identify which factors influence decisions to use it.

Method

A qualitative grounded theory (GT) design was used for this study. GT is “concerned with psychosocial processes of behavior and seeks to identify and explain how and why people behave in certain ways, and in similar and different contexts” (Foley & Timonen, 2015, p. 1197). The initial purpose was to describe core variables, possibly describe a basic social process underlying the experience of urban patients connecting with healthcare providers, and to allow patient perceptions of the phenomenon to emerge from their replies. The data collection method for this study was individual interviews using semi-structured questions designed to allow categories to emerge according to the discovery mode of GT. GT methodology also allows focused follow-up questions to be used during an interview according to topics introduced by participants. Each interview was evaluated according to the constant comparative analysis of the GT method as described by Glaser (1978).

Setting

The setting for this study was Orange County, California. The population of Orange County is the third largest in California, with 72.6% white residents. Foreign-born residents account for 30.4% of the population. The median income in 2018 was $78,145 with 11.1% of the residents living in poverty (Orange County, 2018). These statistics highlight how this study may be unique in the literature for examining patients in an urban setting whose community would be considered privileged by most standards of social determinants of health.

The clinical site for the study was a physician-owned primary care medical group with four medical offices and one urgent care location in cities throughout Orange County. Direct patient services are provided by 12 physicians and 12 APRN family practice nurse practitioners. Ancillary staff included medical assistants and administrative assistants but no back office registered nurses. Since 2014, the medical group has offered technological interfaces including a web-based patient portal, online appointment and lab scheduling, and online chart review. Digital encounters offered include web-based direct patient-to-provider messaging with 24° response (“mouse calls”) and scheduled virtual/video visits. Study interviews took place at two office locations: one in an urban community in the north of the county and one at a beach community in the south.

Sample

Participants were recruited as a convenience sample from adult patients between the ages of 18 and 64 years old who were seeking face-to-face appointments with primary care providers. All reasons for visits and diagnoses were accepted, excluding pregnant and nursing women or patients who were unable to provide informed consent. Recruitment strategies included providing information flyers placed at the reception desks and personal invitations to participate when patients checked in for an appointment. As a convenience sample, there was no attempt to enroll patients who were representative of the social demographics of the medical group or of Orange County, California. A heterogeneous sample of participants was sought without regard to any experience with telehealth because one of the desired outcomes was to learn about their perceptions and decision-making processes, whether they had ever used telehealth or not.

Twenty-six interviews were obtained, of which 21 met inclusion criteria and provided saturation of the dataset. For the 21 included participants, the age range was 23 to 65 (mean 50.1 years). Participants by age were as follows: 25% under 50 years, 55% between 50–59 years, and 20% between 60‑65 years. Gender was evenly divided with 11 female and 10 male participants. Race was predominantly white at 80%, 15% other, and 5% African-American. Ethnicity was identified as Hispanic for 5% of the participants. Employed participants accounted for 65% of the interviews. Marital status was disclosed by 75% of the participants: 40% were married, 30% single, 5% divorced, and 25% declined to state. Excluded interviews included one new patient who had not yet received onboarding orientation to the telehealth options offered by the medical group and four patients who were older than the maximum age criteria. Various crosstab queries for chi-square tests were run on the demographics using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 but no significance was identified due to the small size of the sample.

Data Collection

Data from study participants were collected over a two-week period during standard office hours at the end of December 2018 and beginning of January 2019. A semi-structured interview guide used at each interview was developed based on findings from the literature and with input from the medical group’s physicians. Interviews ranged from 15 to 35 minutes in length. Data were collected by the researcher during individual interviews by attentive listening with minimal notetaking. Immediately upon conclusion of each interview, the researcher created a summary recording from notes and memory. Summary recordings were transcribed using N-VIVO Transcription (QSR International, 2018). Transcriptions were verified against the recordings and edited for accuracy as needed. The transcriptions became the primary source of data analysis.

The methodology for data analysis was the constant comparative analysis of the transcribed interview summaries using open, thematic, and selective coding. All transcripts were initially printed and bound together to facilitate first-pass initial coding. As each successive transcript was analyzed, emerging themes were compared with the previously coded interviews. Ideas and themes were grouped into categories representing the researcher’s thematic syntheses using Banning’s ecological sentence synthesis (ESS) approach to writing thematic sentences (Sandelowski & Lehman, 2012). With an ESS approach, individual themes are converted into prepositional phrases, which are then linked together in a single sentence that describes the emerging categories. The ESS as used in this study captured complete statements from all interviews in a digital manner that became the basis for highly detailed analysis. The ESS data were entered into MS Excel 365, where analysis was accomplished using the pivot table functionality. The data were then imported into MS Access 365 for further generation of thematic statements using the data query and reporting utilities of the software. The ESS sentences served as a basis for writing the thematic statements.

Open coding produced 31 categories. Relationship patterns were noted, and conceptual mapping was used to further refine and sort the data into primary and secondary categories. Memos were created to document progress with the constant comparative analysis of the interviews and ESS. Redundancy of information, or saturation of the dataset, was suspected after the 12th interview and achieved after the 15th interview. An additional six interviews were obtained for confirmation of saturation. Data analysis and comparison continued until all categories were saturated.

Trustworthiness for this study was based on the four criteria for qualitative research as established by Lincoln and Guba (1985):

- credibility was used in place of internal validity – findings were reviewed with several participants and medical group staff who confirmed the truth and accuracy of the findings,

- transferability in place of external validity – findings may be reflected in other populations, primarily confirmed through future research, but findings were also confirmed at a poster presentation of the 2019 AAACN national conference,

- dependability in place of reliability – findings are consistent with the data, as documented by an audit trail (memos and sequential conceptual maps) of the development, process, and evolution of the study results, and

- confirmability in place of objectivity – findings are based solely on participants’ responses as documented in the analysis audit trail.

These operational techniques were successfully applied to establish rigor for this study.

Results

A basic social process, the theory of weighing options, emerged from the data. The data produced the key factors and contexts for knowing this phenomenon. The process of weighing options explains how patients balance “hassle factors” of urgency, timing or scheduling, distance, convenience, transpersonal relationships, and various technical aspects when selecting an encounter type. When all factors show a benefit for telehealth, telehealth may be selected.

The major themes that emerged from the data were organized into the structure of weighing options. Two major themes were identified that influenced the basic social process: contextual factors and personal factors. Contextual factors consisted of such concerns as the reason for visit, the perceived sense of urgency, and a consideration of pre-existing knowledge, values, and behaviors. Personal factors consisted of two sets of variables: negotiable variables affecting selection of appointment type (timing/scheduling, distance, convenience, and transpersonal relationships) and technology variables (devices, skills, and confidence in technology privacy and security). The negotiable and technology variables together constituted the main categories of concern, named by one patient as the hassle factors.

Of special note, within the negotiable personal factors, was the identification of the theme of transpersonal relationships. Comments were coded that mentioned the relationships patients enjoyed with providers, the warm and supportive engagement during a visit, and feeling cared for. Every participant commented on the high level of caring demonstrated by the physicians and nurse practitioners in the practice. Transpersonal factors were mentioned, sometimes emphasized, by all participants and were saturated across all subjects as the most coded category.

Minor themes identified awareness of available options and use of technology by complexity level. Kilbridge, Hood, and Levinthal (2014) noted that telehealth modalities range in five levels of complexity:

- lowest: email, texting

- low: data exchange chart/lab review, data sharing

- moderate: telepresence video visits

- high: remote monitoring

- highest: real-time interventions such as telesurgery

The medical group in this study provided the first three levels; however, study participants engaged primarily with only the first two. Study participants were classified as unaware nonusers, aware partial users, aware nonusers, but only two were aware users. Many subjects stated they were unaware of the full range of available telehealth modalities, yet technical instruction brochures and six-foot banners were located at the check-in and checkout desks at all patient areas in the medical offices. At the conclusion of the interview, most participants indicated a desire to know more about how to use the various options.

The Theory of Weighing Options

The discovered theory, weighing options, has a starting and ending point in time. The starting point is the moment the patient decides to seek care to resolve the current main concern, which leads to the basic social process of weighing options. The endpoint is when the patient connects with the provider. The weighing options process starts with determining the urgency of the main concern; if it is urgent, the patient seeks immediate attention in person and goes no further in the process. If the need is routine or emergent, the patient filters the present main concern through the three contextual factors of knowledge, values, and behaviors (Artinian, West, & Conger, 2011). The knowledge factor includes the personal history of known factors about the current condition and provider, the values factor examines what is important to the patient for resolving the main concern, and the behaviors factor provides a review of past behaviors or what one is willing to do in the present to resolve the main concern. Next, the patient proceeds with balancing pertinent hassle factors of timing (scheduling), convenience, distance, and transpersonal relationships of the current concern. The patient’s final evaluation influencing the decision to schedule a telehealth or in-person visit is a consideration of personal skills with the technology and confidence in technological privacy and security as offered by the medical group. After weighing the options, one of three outcomes is possible:

- If hassle factors are favorable and the perception that no direct physical care is needed, then the options are weighted in favor of telehealth and a telehealth encounter may be selected.

- If hassle factors are overwhelming or the perception that direct physical care is needed or desired, then an in-person office visit will be scheduled.

- If hassle factors are equal and in balance, the data suggest that the type of visit may be chosen based on the transpersonal experience desired in the moment (see Figure 1, Theory of weighing options).

Figure 1: Theory of Weighing Options

Contextual Factors

The initial process of weighing options consisted of contextual factors related to the main concern (reason for visit) for the current appointment and the sense of perceived urgency. Reasons varied from routine scheduled appointments, acute minor conditions, and acute emergent conditions. Sometimes the context originated with medical group staff: “My appointment today was because I got a phone call that I needed to come in and follow-up on my labs. At the time they called, they scheduled today’s appointment.” Another context was that it was time for an annual physical: “Today’s appointment was to schedule my mammogram, but I was told I needed a well woman checkup first. I guess my insurance changed the requirements on that.” Occasionally there were emergent conditions such as when a specialist referred the patient to be seen by the primary care physicians on the same day: “My blood pressure was so high at my ENT’s office today that they called and got an appointment for me.”

Hassle Factors

Negotiable variables of the hassle factors could be convenient or a nuisance, present or absent, in the context of resolving the current main concern. These hassle factors included distance to the office in mileage, travel time, and the convenience of getting there. “Driving the distance is worth it to be seen by these wonderful doctors and nurse practitioners.” In contrast, another patient who lived within walking distance commented, “The convenience and location make it not so important or even pertinent to have a virtual visit.” Initially, hassle factors were understood to be those of logistical concerns. Later analysis revealed that all factors taken under consideration by the patient constituted hassle factors of one kind or another. One patient had completed the transition to the online appointment scheduling and stated, “I never use the phone system [of the medical group] anymore. I handle all of my communication needs through the phone app.”

Technological variables of the hassle factors reflected a wide range of concerns from patient-owned hardware such as personal smartphones or computers, the patient portal as provided through the medical group website, the custom medical group smartphone app, and the proprietary HIPAA-compliant virtual visit app. Concerns were also noted relating to privacy and security about the electronic healthcare record across telehealth modalities. All participants identified themselves or a family member as competent users of laptops or computers and personal devices such as an iPad or a smart phone. However, one participant was adamant stating the reasons he would never use telehealth even though he was a highly competent and skilled user of technology:

I can’t think I’d ever embrace telehealth. Other than owning a smart phone, I own no other technology anymore. I use the library computer as needed. I am most concerned with electronic healthcare records’ security and privacy. I can’t avoid having an electronic chart, but I do not want to add additional nodes to my chart.

Another patient stated, “I access the webpage via my phone all the time. I’m a heavy user of both messaging my doctors and using ‘mouse calls’ [secure messaging]. It’s especially convenient when I’m out of town.” For those who did use telehealth, their responses were summed up by the patient who said, “Having these options to reach my doctor are a godsend.”

Discussion

This study confirmed that patients are very deliberate about seeking healthcare, weighing options anew each time a healthcare concern exceeds their own ability to manage by themselves. Discovering the weighing options theory provided insight to each of the study questions. For the first question “How do patients select any type of appointment when seeking care?”, weighing options explains the process for selecting telehealth versus in-person appointments as needed to resolve the main concern in the moment. The participants made clear that this process starts anew with each ambulatory encounter before any contact is made with the provider. Selecting telehealth for the same condition a month ago did not guarantee that telehealth would be selected for the same condition in the future. For the second question, “How do patients perceive and use available telehealth options?”, one remarkable finding was the great fondness of the study participants for the doctors and nurse practitioners in the medical practice. Every participant stated in one way or another that coming to the office in person met a transpersonal relationship need they were unwilling to give up for telehealth unless other hassle factors were overwhelming. The final question of this study, “Under what circumstances might telehealth be useful in the future?” was answered when participants identified certain hassle factors such as traffic or late-night convenience as reasons to use telehealth going forward. As experience with telehealth increases and providers guide patients in the types of circumstances appropriate for telehealth, the weighing options process should lead to increased selection of telehealth encounters.

Given the additional insight from this study into the importance of the transpersonal relationship, weighing options also provided a possible explanation for why rural studies showed patient acceptance of and satisfaction with telehealth: the hassle factors of traveling long distances in a rural setting far outweighed the transpersonal relationship need. However, after identifying the importance of transpersonal factors among the urban participants in this study, rural studies were reviewed again specifically for transpersonal factors. It was noted that the majority of rural telehealth studies report lack of patient access to broadband connections outside of town with low usage of personal computing devices. Thus, the rural telehealth model provides access for patients to use the technology and broadband in the office of their local provider to connect to the distant provider; the transpersonal relationship with the primary care doctor remains intact on the patient side of the telehealth encounter. In other words, rural patients did not have to negotiate giving up the transpersonal relationship with their primary care providers to use telehealth.

Implications

The Triple Aim initiative from the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) (Institute of Healthcare Improvement, 2019) provides a framework for optimizing health system performance across three dimensions: improving the patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of health care. Implementing telehealth in primary care meets all three of these dimensions. Inquiring about adult perceptions using telehealth was an effort to understand the dimension of the patient experience concerning quality and satisfaction. The discovered theory, weighing options, explains the process patients use to decide how to engage with health care before connecting with anyone on the health care team. Weighing options identifies potential areas for staff support for the patient experience with telehealth. These areas include proactively guiding the patient decision-making process, providing patients with training and necessary skills prior to using telehealth, supporting telehealth during use, and reassuring patients that the transpersonal relationship will be preserved across technology. The telenurse and NIS in ambulatory care are well poised to support these key areas.

Supporting the Patient Experience

Studies have shown that providing patients with training and skills of both the necessary technology as well as the reasons for telehealth is important to initiate use of telehealth and must be coupled with intermittent reinforcement to maintain telehealth as a viable option. Unless technical skills are used frequently, competencies fade over time and patients will revert to in-person office visits (Broens et al., 2007; Hoppszallern, 2016). Casey (2016) found a positive effect of hands-on training for increasing patient interaction with personal health record (PHR) interfaces such as patient portals. In Casey’s study, both comfort level with computer use and use of the personal health record increased following live training, showing the importance of training as a factor in patient acceptance. Unfamiliarity with the technology and interface represents a significant hassle factor that patients may not be able to overcome without continued direct support from the office staff.

Reasons for visits must be part of patient training whether in person, online, or with telehealth brochures or leaflets. Patients in the current study were unable to discern which reasons could be an option for a telehealth visit. Kayyali, Hesso, Ejiko, and Gebara (2017) evaluated telehealth leaflets and found gaps in providing sufficient information to be useful to patients. They identified content that patients wanted in the leaflets, such as assurances regarding the technology involved and technical support, cost, confidentiality, and personal choices. Patients were hesitant to choose telehealth when these knowledge gaps were present.

Preserving the Transpersonal Relationship

Because every participant in this study commented on the positive relationships enjoyed with the staff at the study site, this satisfaction emphasized one major challenge with implementing telehealth: how can nurses and healthcare providers demonstrate patient-centric caring and support when physical proximity to patients becomes virtual? Competencies have been proposed for providers and nurses to learn new communication processes for digital media with an understanding of how interpersonal communication changes in the presence of technology (Fathi, Modin, & Scott, 2019; Barbosa & Silva, 2017). Patients still need a nurse when using telehealth, perhaps one who expresses even more TLC than when in person.

Role of the Telenurse

The current AAACN Scope and Standards of Practice for Professional Telehealth Nursing (2018) provide guidance for telenursing practice in ambulatory care to “identify patient needs and resources available to achieve desired outcomes” (p. 44). The 2012 AAACN position statement on ambulatory care nursing included a similar observation that “telehealth nursing services assist patients in making informed decisions regarding access to care, monitor patients’ conditions, and manage care for both acute and chronic illnesses” (p. 234). The role of the telenurse in supporting patients using telehealth continues to increase in breadth and scope as innovative applications of technology expand the field of ambulatory nursing. Notably, telenursing begins at the point of contact, when weighing options ends. Nevertheless, with heightened awareness of patient hesitancy to use telehealth, the telenurse can provide proactive support to encourage using telehealth in the future.

Role of the Nurse Informatics Specialist (NIS)

The role of the NIS continues to evolve to include the new health paradigms of connectivity between care providers and patients (Nagle, Sermeus, & Junger, 2017). Until recently, the role of the NIS focused on supporting EHR system acquisition, implementation, and maintenance within health care organizations. With the increasing use of telehealth in the ambulatory world, and the coordination of patient care from hospital to ambulatory settings, it is a natural step for the NIS to offer those same skills in the ambulatory world. Nagle et al. (2017) noted, “…nursing input and informatics expertise will be important to ensure appropriate and safe use of these [telehealth] tools. As individuals and their families become more active participants in their care through the use of applications and devices to connect with providers, they will likely also need expertise and support from the NIS” (p. 216). The nurse informaticist practicing in primary care settings will need to be proficient in the technology of ambulatory telehealth and support of a variety of end users including patients, providers, and medical practice administrators. The nurse informaticist must also stay current with the rapidly changing professional standards and governmental regulations that include telehealth expansion with potential implications for licensure when remote patients are in another state (National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 2014).

Francis (2017) noted that nursing informatics is fundamentally anchored within the context of nursing as a caring science, with caring as an essential core factor in the practice of technology. When the NIS ensures that caring, as a core nursing value is not diminished or compromised by technology, this action maintains the transpersonal impact so desirable to both patients and clinicians. Although nurses were not interviewed in this study, participant comments indicated that there are many opportunities for supportive nursing actions, such as helping patients download the clinic app onto personal smart phones or identifying clinical circumstances appropriate for using telehealth.

Limitations

One limitation of the project was the setting at a physician-owned medical practice in an affluent urban setting. A second limitation was the small convenience sample of patients recruited from only two of the five office locations for the medical group. Participants may not have been representative of either the full client population of the medical practice or the county population. Therefore, the setting and participants of this study may not be generalizable to other types of medical practices or populations, whether urban or rural. A third limitation may have been the result of possible recall bias of the participants for remembering past motivations when selecting visit types and of the researcher when recording the summary immediately following the interview.

Recommendations

Weighing options is a basic social process that takes place when the patient determines that a current health concern requires contact with a health care provider, guides the determination of the type of encounter desired, and ends when contact is made with the provider. Nearly all health care team initiatives, interactions, and competencies pertaining to telehealth take place when the patient-provider contact begins. Since this study examined patient perceptions prior to contact, recommendations are made based on inferences from the interviews.

Onboarding Patients and Staff to Telehealth

The results suggest future research is warranted for an evidence-based practice project to discern best practices when onboarding patients to and determining patient satisfaction with telehealth. Each phase of weighing options and each individual hassle factor could be studied with a focus on evaluating cost-benefit outcomes. For example, what is the influence of the hassle factor comparing chronological travel distance instead of geographical distance?

For patients, Iafolla (2019) observes that a little guidance and education about telehealth offerings can generate excitement to try it. Iafolla’s suggestions include emphasizing the benefits, sharing written materials, avoiding the use of medical jargon, providing opportunities to ask questions, starting a conversation about telehealth at the end of an office visit, showing how telehealth works with live demos or checklists or online videos, and being clear about what equipment is needed.

For primary care staff, how would periodic educational reinforcement for them influence patient engagement of telehealth? Amaral (2017) emphasized the importance of preserving the existing culture in the practice and finding out what matters to staff, as well as to patients. In the present study, participants made many comments on how much they loved the staff and providers in the medical group. Somehow, the impact of telehealth on the local healthcare culture needs to retain the level of satisfaction patients experience in person. Sarasohn-Kahn (2014) noted, “Patients will be engaged when engagement is personally meaningful, trusted, easy and convenient” (p.7). Awareness, engagement, and education for all involved are essential to program success.

Communicating Caring

There is also an opportunity to determine how ambulatory providers communicate caring and support during and with virtual encounters. Ten studies in an integrative literature review recommended that nurses and providers should receive specific training to develop abilities and communication skills appropriate to overcome virtual barriers of time and distance (Barbosa, Silva, Silva, & Silva, 2016). Mataxen and Webb (2019), noting that effective communication skills using telehealth modalities continue to be an ongoing issue, suggested using either the AAACN process of telephone nursing model or Nagel and Penner’s conceptual model for telephone nursing. Both models feature guidance for interacting with a patient who is connected only by technology.

Telenurses and Nurse Informatics Specialists (NIS)

Fathi, Modin, and Scott (2017) noted the need for new practice models in which ambulatory care nurses and informatics nurses both have an advanced role to play leading telehealth integration for the redesign of primary care practices. Without adequate training of clinicians in telehealth technologies, the potential of telehealth cannot be fully realized. The AAACN has established competencies and practice standards for telehealth nursing which includes seven comprehensive key competency areas (AAACN, 2018).

To determine staff competencies essential to telehealth, Houwelingen, Moerman, Ettema, Kort, and Cate (2016) convened a panel of 51 experts consisting of nurses, nursing faculty, clients, and technicians in a Delphi study. The panel achieved consensus identifying six core competencies encompassing 14 related “nursing telehealth entrustable professional activities” (NT-EPAs). For the telehealth competent nurse, knowledge, attitudes, and skills required across the NT-EPAs were identified. Examples of NT-EPAs that target patient adoption of telehealth include supporting patients in the use of technology, training patients in the use of technology to strengthen their social network and assessing patient capacity. The following selected examples from the Delphi study highlight NT-EPA competencies with corresponding skills unique to telehealth. Increased engagement by primary care patients could be realized by incorporating these skills into practice by the ambulatory telenurse or NIS:

- Knowledge

- Knowledge of the (clinical) limitations of telehealth

- Knowledge about what to do if the technology does not work

- Attitudes

- Conveys empathy through videoconferencing by facial expression and verbal communication

- Promotes privacy and confidentiality in videoconferencing

- Enhances the confidence of the patient in the deployed technology

- Technological skills

- Trains the patient to use the equipment

- Checks equipment for functionality

- Communication skills

- Communicates clearly in videoconferencing and knows what to do to enhance contact (e.g., use of voice, light, background)

- Puts patients at ease when they feel insecure about using technology

- Implementation skills

- Assesses whether telehealth is convenient for the patient by the use of established criteria (for example, cognitive ability, technological skills)

Finally, how will telenurse and NIS competencies with telehealth modalities be assured with future nurses? Skiba (2015) noted that “…nurses need more experience…using digital tools…and to gain greater understanding of how patients, families, and caregivers use these tools. … Nurses must understand how to use digital tools to foster patient activation and engagement… [as well as] gain an understanding of how patients themselves use these tools” (p. 201). Regardless of the setting or the role, it is critical to establish “an authentic, caring relationship with a patient when the interaction is limited to a presence on the screen with a voice and in the absence of the traditional hands-on human connection” (Adzhigirey et al., p.3).

AAACN standards for professional telehealth nursing and ANA standards of nursing informatics practice that align with these observations are identified below for telehealth-competent nurses. While the name of the standard is the same from both organizations, the skills list within is specific for the role.

- Provide support: assess each patient’s knowledge, values, preferences, behaviors and abilities with technology and offer individualized guidance (Standard 5b: Health Teaching and Health Promotion)

- Maintain the transpersonal relationship: connect with patients using digital communication competencies in all virtual interactions (Standard 11: Communication)

- Increase awareness: describe the potential benefit of telehealth to patients (Standard 15: Resource utilization)

- Develop competency with telehealth technology: demonstrate proficiency with the specific telehealth applications offered to patients (Standard 16: Environment)

Conclusion

This study was successful in determining from the interview responses how urban patients in one primary care medical practice weigh options when selecting an encounter type whether telehealth or an in-person office visit. The responses also indicated that while lower complexity technology is acceptable to many patients, the more moderate complexity options such as virtual visits are viewed with skepticism and concern. Moderate- to high-complexity modalities may need regular hands-on training to initiate and maintain usage.

Established telehealth nurse competencies can be used to support patients presently in anticipation of future encounters when patients will be weighing options to choose how they will interact with their providers. There are opportunities for the NIS to expand practice into the ambulatory primary care setting and to provide collaborative consultation between patients, providers, staff, and ambulatory tech support. Ultimately, ambulatory care nurses and providers play an important role in preparing patients to resolve hassle factors at the time when patients are weighing options for selecting the best care in the moment.

Citation: West, K. & Artinian, B. (Fall 2019). Weighing options: Perceptions of adult patients accessing telehealth in primary care. Online Journal of Nursing Informatics (OJNI), 23(3)

The views and opinions expressed in this blog or by commenters are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of HIMSS or its affiliates.

Online Journal of Nursing Informatics

Powered by the HIMSS Foundation and the HIMSS Nursing Informatics Community, the Online Journal of Nursing Informatics is a free, international, peer reviewed publication that is published three times a year and supports all functional areas of nursing informatics.

Katharine West, DNP, MPH, RN-BC, CNS, PHN, is certified as an advanced facilitator for the University of Phoenix Southern California campus undergraduate and graduate nursing programs. A Phi Beta Kappa graduate with a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Southern California and a Bachelor of Science in nursing degree from Excelsior University, Dr. West earned master’s degrees from the University of California, Los Angeles (Master of Public Health) and Azusa Pacific University (Master of Nursing), and a Doctorate of Nursing Practice from the California State University Northern Consortium. Her expertise in nursing includes an advanced practice license as a parent-child health clinical nurse specialist and a certified public health nurse. She is ANCC board-certified in nursing informatics and holds a post-graduate certificate in public health informatics from the University of Illinois - Chicago. Dr. West has broad clinical experiences ranging from inpatient care to insurance-based case management and maternal-child home health & hospice care. Experienced in nursing and public health informatics, she was on the team that implemented a statewide public health program for newborn hearing screening in California. She holds EPIC Systems certification with 13 years’ experience as a clinical systems analyst for Kaiser Permanente’s electronic healthcare record. At Kaiser, she led surgical specialty domains in the development and maintenance of custom informatics solutions. West is a contributing author to books on qualitative research and rural nursing, has created online content for textbooks on maternal-newborn nursing, and served as a reviewer for Englebardt’s leading healthcare informatics text. Dr. West has taught nursing from vocational to graduate levels with an emphasis on public health and informatics nursing. Her extensive experience coupled with her scholarship and abilities to communicate make her an outstanding educator of computer technologies applied to health care. Her podium and paper presentations on using computer technologies in nursing are enthusiastically received at local, regional, national, and international conferences. Dr. West’s varied and dynamic experience is distinctive among nurses, as she discerns health care trends, translates them into pragmatic learning opportunities, and articulates the implications for clinical care.

Barbara M. Artinian, PhD, RN, is professor emeritus of the School of Nursing at Azusa Pacific University. Dr. Artinian has taught courses in community health nursing, family theory, nursing theory, and qualitative research methodology. She developed the Artinian Intersystem Model based on the work of Alfred Kuhn and Aaron Antonovsky. She published several articles about the model in the 1990s that culminated in the publication of the book entitled The Intersystem Model: Integrating Theory and Practice by Sage Publications (1997). The model has been used in a variety of practice settings and was used by David Taylor as a framework for his doctoral dissertation work done at the University of Wollongong in Australia. This book presents work done by students who were introduced to the model during their studies or from reading the publications about the model. Dr. Artinian has served as advisor for grounded theory research for five doctoral and 24 master-level students. The work of these students was reported in the book Glaserian Grounded in Nursing Research: Trusting Emergence by Springer Publishing Company (2009). This book has received excellent reviews. Dr. Artinian grew up in Wisconsin and graduated from Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois. She attended Case Western Reserve University, where she received a degree in nursing. She completed her graduate work at the University of California, Los Angeles, earning a Master of Science in nursing degree. At the University of Southern California, she earned a Ph.D. in sociology with a major emphasis in family theory. She completed a postdoctoral research fellowship at the University of California, San Francisco, in the area of chronic illness and was introduced to the methodology of grounded theory at that time. Her knowledge of grounded theory research has enhanced her understanding of the process of the Artinian Intersystem Model.

References

Abrams, K., Burrill, S., & Elsner, N. (2018). What can health systems do to encourage physicians to embrace virtual care? [Infographic]. Deloitte Insights.

Adzhigirey, L., Berg, J., Bickford, C. J., Broadnax, T., Denton, C., Leistner, G., . . . Smedley, L. (2019). Telehealth nursing: A position statement 2019 (Telehealth Special Interest Group - ATA). 1-13.

Agate, S. (2017). Unlocking the power of telehealth: Increasing access and services in underserved, urban areas. Harvard Journal of Hispanic Policy, 29, 85-96.

Amaral, A. (2017). How to make sure a telehealth program pays off. HealthData Management.

American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing (AAACN). (2012). American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing position statement: The role of the registered nurse in ambulatory care. Nursing Economic$, 30(4), 233-239.

American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing (AAACN). (2018). Scope and standards of practice for professional telehealth nursing (6ed.). Pitman, NJ: Author.

American Nurses Association (ANA). (2015). Nursing Informatics: Scope and Standards of Practice (2ed.). Silver Spring, MD: Author

Arellano, M. (2014). Nursing informatics reaches well beyond acute care. Nursing2019, 44(11), 21-22. doi:10.1097/01.Nurse.0000454968.72009.29

Artinian, B. M., West, K. S., & Conger, M. (2011). The Artinian intersystem model: Integrating theory and practice for the professional nurse (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer Pub. Co.

Barbosa, I.D.A., & Silva, M. J. P. (2017). Nursing care by telehealth: What is the influence of distance on communication? Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 70(5), 928-934. doi:10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0142

Barbosa, I.D.A., Silva, K.C.C.D., Silva, V.A., & Silva, M.J.P. (2016). The communication process in telenursing: Integrative review. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 69(4), 765-772. doi:10.1590/0034-7167.2016690421i

Barnett, M. L., Ray, K. N., Souza, J., & Mehrotra, A. (2018). Trends in telemedicine use in a large commercially insured population, 2005-2017. JAMA, 320(20), 2147-2149. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.12354

Broens, T. H. F., Veld, R.M. H. A.H., Vollenbroek-Hutten, M. M. R., Hermens, H. J., Halteren, A. T. V., & Nieuwenhuis, L. J. M. (2007). Determinants of successful telemedicine implementations: A literature study. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 13(6), 303-309. doi:10.1258/135763307781644951

California Legislative. (2016). Telehealth. California Business and Professions Code § 2290.5.(a)(6).

Casey, I. (2016). The effect of education on portal personal health record use. Online Journal of Nursing Informatics, 20(2), 9-9.

Chenitz, W. C., & Swanson, J. M. (1986). From practice to grounded theory: Qualitative research in nursing. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley.

Edwards, L., Thomas, C., Gregory, A., Yardley, L., O'Cathain, A., Montgomery, A. A., & Salisbury, C. (2014). Are people with chronic diseases interested in using telehealth? A cross-sectional postal survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(5), e123. doi:10.2196/jmir.3257

Farr, C. (2018). Why telemedicine has been such a bust so far. CNBC Newsletters - Health Tech Matters.

Fathi, J. T., Modin, H. E., & Scott, J. D. (2019). Nurses advancing telehealth services in the era of healthcare reform. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing (OJIN), 22(2). doi:10.3912/OJIN.Vol22No02Man02

Foley, G., & Timonen, V. (2015). Using Grounded Theory method to capture and analyze health care experiences. Health Services Research, 50(4), 1195-1210. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12275

Francis, I. (2017). Nursing informatics and the metaparadigms of nursing. Online Journal of Nursing Informatics, 21(1), 8-1.

Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Haghi, M., Thurow, K., & Stoll, R. (2017). Wearable devices in medical Internet of Things: Scientific research and commercially available devices. Healthcare Informatics Research, 23(1), 4-15. doi:10.4258/hir.2017.23.1.4

Heath, S. (2017). 77% of patients want access to virtual care, telehealth. Patient Engagement HIT.

Hoppszallern, S. (2016). Telehealth: Bringing health care to the patient. Hospitals & Health Networks, 90(4), 17-17. Retrieved from Ebscohost.

Houwelingen, C. T. M., Moerman, A. H., Ettema, R. G. A., Kort, H. S. M., & Cate, O. (2016). Competencies required for nursing telehealth activities: A Delphi-study. Nurse Education Today, 39, 50-62. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2015.12.025

Iafolla, T. (2019). 7 steps to educating patients about telehealth [Blog].

Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI). (2019). The IHI triple aim. Retrieved from http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx

Kayyali, R., Hesso, I., Ejiko, E., & Gebara, S. N. (2017). A qualitative study of telehealth patient information leaflets (TILs): Are we giving patients enough information? BMC Health Services Research, 17, 1-11. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2257-5

Kilbridge, P., Hood, E. H., & Levinthal, N. (2014). Telemedicine in the era of population health management. Retrieved from Washington, DC: https://www.advisory.com/research/health-care-it-advisor/research-notes…

Li, J., & Wilson, L. S. (2013). Telehealth trends and the challenge for infrastructure. Telemedicine and e-Health, 19(10), 772-779. doi:10.1089/tmj.2012.0324

Lincoln, Y. & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mataxen, P. A., & Webb, L. D. (2019). Telehealth nursing: More than just a phone call. Nursing2019, 49(4), 11-13. doi:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000553272.16933.4b

Nagle, L. M., Sermeus, W., & Junger, A. (2017). Evolving role of the nursing informatics specialist. Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 232: 212-221. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-738-2-212

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (NCSBN). (2014). The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) position paper on telehealth nursing practice. https://www.ncsbn.org/14_Telehealth.pdf

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2019). Development of the national health promotion and disease prevention objectives for 2030 | Healthy People 2020. Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People/Development-Hea…

Orange County. (2018). About the county: Info OC: Facts & figures. Retrieved from http://www.ocgov.com/about/infooc/facts

Polinski, J. M., Barker, T., Gagliano, N., Sussman, A., Brennan, T. A., & Shrank, W. H. (2016). Patients’ satisfaction with and preference for telehealth visits. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(3), 269-275. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3489-x

Poulsen, K., Roberts, L., Millen, C., Lakshman, U., & Buttner, P. (2014). Satisfaction with rural rheumatology telehealth service. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 66, S508-S508.

QSR International. (2018). NVivo transcription. Retrieved from https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/nvivo-products/transcription

Sandelowski, M., & Leeman, J. (2012). Writing usable qualitative health research findings. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1404-1413. doi:10.1177/1049732312450368

Sarasohn-Kahn, J. (2014). The state of patient engagement & health IT. Retrieved from https://www.himss.org/state-patient-engagement-health-it

Skiba, D. J. (2015). Connected health: Preparing practitioners. Nursing Education Perspectives (National League for Nursing), 36(3), 198-201. doi:10.5480/1536-5026-36.3.198

Sweeney, E. (2017). Policy researchers: Urban patients need access to telemedicine, too. Retrieved from https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/mobile/telemedicine-rural-urban-access…

Thakar, S., Rajagopal, N., Mani, S., Shyam, M., Aryan, S., Rao, A. S., . . . Hegde, A. S. (2018). Comparison of telemedicine with in-person care for follow-up after elective neurosurgery: Results of a cost-effectiveness analysis of 1200 patients using patient-perceived utility scores. Neurosurgical Focus, 44(5), E17. doi:10.3171/2018.2.Focus17543

Umland, B., Ferreira, E., & Lown, B. (2018). Everyone wants telemedicine. So why aren’t your employees using it? Retrieved from https://www.mercer.us/our-thinking/healthcare/everyone-wants-telemedici…

Walmart, Inc. (2019). Video doctor visits. Retrieved from https://one.walmart.com/content/uswire/en_us/me/health/health-programs/…

Wicklund, E. (2017). Telehealth barriers should be defined by access, not geography. mHealth Intelligence. Retrieved from https://mhealthintelligence.com/news/telehealth-barriers-should-be-defi…

Zheng, H., Tulu, B., Choi, W., & Franklin, P. (2017). Using mHealth app to support treatment decision-making for knee arthritis: Patient perspective. eGEMs (Generating Evidence & Methods to improve patient outcomes), 5(2), 7. doi:10.13063/2327-9214.1284